I have heard of a number of examples of wasteful government spending, like:

A recent audit revealed that between 1997 and 2003, the Defense Department purchased and then left unused approximately 270,000 commercial airline tickets at a total cost of $100 million.

A recent audit revealed that employees of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) diverted millions of dollars to personal purchases through their government-issued credit cards. Sampling 300 employees’ purchases over six months, investigators estimated that 15 percent abused their government credit cards at a cost of $5.8 million. Taxpayer-funded purchases included Ozzy Osbourne concert tickets, tattoos, lingerie, bartender school tuition, car payments, and cash advances.

Waste Examples: Hookers For Jesus ($530,190); tai chi classes in senior centers ($671,251); creating outdoor gardens at schools ($1.6 million); and space alien detection ($7 million). Taxpayers funded story time at laundromats ($248,200); sex education for prostitutes in Ethiopia ($2.1 million); a social media war on tanning beds ($3.3 million); webcast-livestreamed eclipses ($3.7 million); and subsidized the airport on Martha’s Vineyard ($12 million).

Ivy League, Inc. The eight Ivies received $9.8 billion in federal grants despite having a collective endowment of $140 billion – which was up $20 billion since 2016.

I think you get the idea. A recent article on TheConversation.com talks about an idea for a governmental program that sounds a little edgy, but I think merits discussion.

Farmland Drought

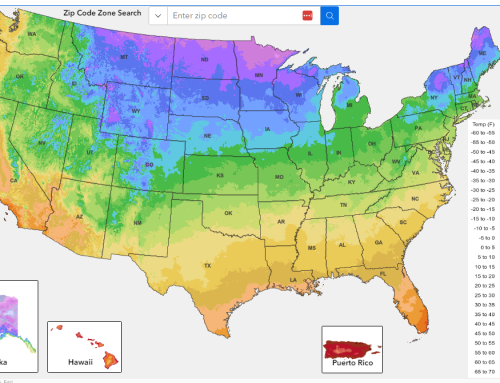

The lack of adequate water reserves to quench the thirst of the southwest is well known. John Oliver has a recent segment that shows many of the short sighted mistakes and poor decisions that “we” have made in dealing with water in this region. (My favorite is an agreement that allows for the distribution of 15 million acre feet of water from a resource that contains 12 million acre feet. I wonder why there is not enough water.)

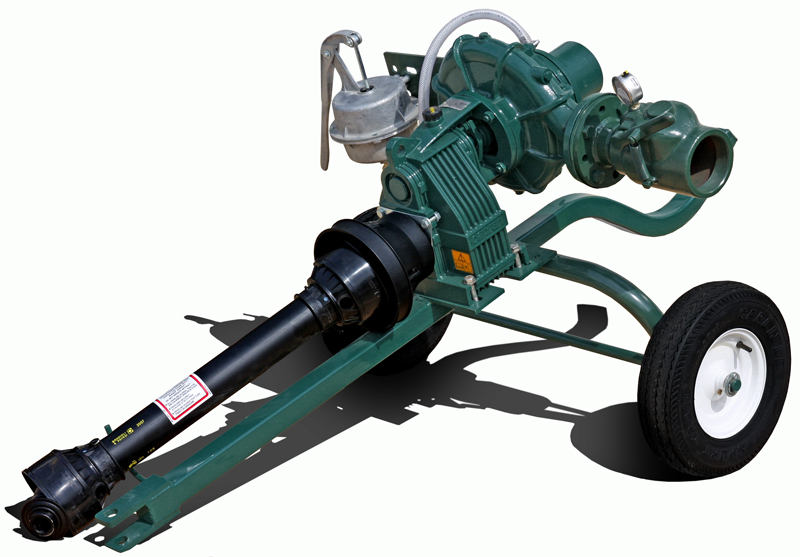

The biggest use of water in this region is agriculture. It is estimated that as much as 80% of the water in this region is consumed by farming interests. One of the most promising technologies to reduce water use is drip irrigation, which can dramatically reduce the amount of water used per acre when compared to farms that utilize either flood systems or pressurized center pivot systems.

Drip irrigation can reduce the amount of water lost from evaporation, percolation into the soil and runoff. “Microirrigation systems use 20% to 50% less water than conventional sprinkler systems.” So why doesn’t everyone use drip irrigation? (Nine times out of ten the answer is money.)

Cost. “Most farms that irrigate are small operations with fewer than 50 acres (20 hectares) and less than $150,000 in annual revenues.”

Robert Glennon, Regents Professor Emeritus and Morris K. Udall Professor of Law & Public Policy Emeritus, University of Arizona, proposes a two pronged approach.

First, Congress would provide funding to the U.S. Department of Agriculture to offer farmers more generous financial incentives to switch to microirrigation systems. The 2021 infrastructure bill contains $8.3 billion to assist western states in adapting to drought and climate change. I believe that this financial aid, with support from the federal Bureau of Reclamation and the USDA, could persuade millions of American farmers to make the move.

Second, to augment the federal program, state, municipal and local interests, including government agencies and private businesses, would create funds to underwrite the entire cost of converting farms to microirrigation. As I envision it, cities could offer to absorb 100% of the purchase and installation costs of microsystems in exchange for a percentage of the water that farmers would save by making the switch.

While this idea has its distractors, on the surface, I believe it has merit and should warrant consideration. Right now the current plan is simply cut the amount of water across all users. A more proactive approach that works directly on the users who consume the most water and helps them reduce their consumption makes sense.

Ask yourself, if we knew what we know today 25 or 50 years ago, would we have embraced a plan that reduced water consumption from the beginning? I like to think so. And the cost to implement conservation is not going to be cheaper tomorrow.

If you would like help with your drip irrigation needs, give us a call today at 517-458-9741.